|

| Photo of Tunick nudescape, Mexico City Zócalo, from bbcmundo.com |

unencumbered musings on naturism, nudity, and the body

|

| Photo of Tunick nudescape, Mexico City Zócalo, from bbcmundo.com |

Nudity is a public health issue, but not for the reasons many people might assume. It is not because of the need to shield bus seats from bare buttocks, or to protect diners at restaurants from pubes in their salads.

No.

Nudity is a public health issue because nudity is the beneficial, natural state of our bodies. The advantages of outdoor skin exposure to the elements are recognized physically and psychologically, yet nudity is most often banished to bathrooms, bedrooms, and other enclosed spaces.

|

| From “Bodies of Water” by Naked Club |

It is true that instead of cash-strapped governments, better endowed entities such as private organizations or companies can finance advertisements or public relations campaigns promoting the benefits of nudity. This is welcome and maybe even profitable for certain of these entities. But only governments have the power to designate vast swaths of public land for nude recreation. This is why it’s important to assist TNS and AANR in working with city, county, state, and federal governments toward that end.

Another proactive stance is to sign the current We The People petition to designate clothing-optional areas of federal lands initiated by Larry Darter of Dallas Nudist Culture Examiner. I’d rather such lands be designated for nude use only, as opposed to clothing optional, but that’s a quibble I didn’t let stand in the way of signing the petition.

Designating more areas for being nude outdoors, on public lands as well as on private property, will help bring more of the population to the “uncovery” that outdoor social nudity not only feels great but is great for you. We should all advocate that a happier, healthier, more nude-friendly population makes for a less stressful, less fearful, more open-minded society.

From a naturist or nude-friendly point of view, what jumps out about these illustrations is that the babies are depicted nude – no need for diapers, no need even for the sash that proclaims the digits of the new year. (Often in this graphic trope, the old man/old year, too, is shown wearing only a sash covering genitals and buttocks). Nowadays, unfortunately and unsurprisingly, baby new year is almost always depicted with diapers, at least in the mainstream media that censor even the nudity of an infant.

Why not take back the idea of a nude baby new year, and link it to a calendar of nude health and wellbeing? January, for example, would be a great month for educating new parents about the dangers and long-term disincentives of circumcision. For a baby new year, January, naturally, would also be the month for promoting not just breastfeeding but also the right of mothers to breastfeed anywhere, and their right to expose as much of their bodies as they want or need in order to do so.

Fellow naturist blogger Robert Longpré has produced a volume called Naked Poetry by the Sea and on the Prairies. The polished, succinct poems of his collection guide us to the naked core of truths both spiritual and physical. These are terrific poems! I had the honor of contributing a brief preface to the volume, which I’m reproducing here below. You can download the volume, which also features striking photographs for each poem, at Smashwords.

Writing poetry is like fishing in a lake of insights. A flash here, a splash there – a bite? Through skill and luck, a practiced fisher can deliver the shimmering sustenance of substance from the depths. Robert Longpré, an expert fisher-poet, has produced a terrific bounty of glittering insights from our unconscious depths in the form of poems that are brief meditations. These poetic meditations share the theme of nudity – how the shedding of clothes, as a return to our natural state, is complicated by modern society, by anxieties and fears, yet can be overcome in the joyous liberation that nudity can bestow us. As Longpré reminds us, “Even standing / naked in front of others / truth is hidden.” Yet in spite of inner anxieties that cloak aspects of our identity, “heaven is a return to the Garden of Eden / and Eden isn’t clothing optional.” In Longpré’s gem-like poems, nudity is often portrayed on the prairie. The wide-open vistas enhance the sense of skyclad freedom for all the prairie’s fauna:

The empty spaces soon filled with

life and colour and sound

with three deer staring back unafraid

of a human wandering naked on the prairie.

Birds, dragonflies, moths, grasshoppers and butterflies

moved with deliberation as though dancing

through the afternoon like the naked wanderer.

Above all, Robert Longpré’s poems form an important link between what we can call a literature of naturism, and a literature of meditation. Of course, writing and also reading poetry are acts of meditation in and of themselves, but Longpré brings the glowing immanence of nude meditation itself to the fore:

Sitting still, listening to breath

travel in and out: a glimpse of

naked soul brings an inner glow

that wraps itself around the naked body

on the cushion.

The example is manifest: read, write, meditate, wander… free from the restrictions of clothing and other arbitrary societal norms. Your journey—physical, spiritual, mental, emotional—will be all the more expansive and profound: to the middle of the open prairie, to the depths of your glittering insights.

She is one of the most memorable characters from one of the most beloved books in the world, and it’s time to recognize her for what she is: a nudist. I’m referring to Remedios la Bella from Colombian Nobel Laureate Gabriel García Márquez’s Cien años de soledad (One Hundred Years of Solitude).

|

|

“El realismo virtual de 100 años de soledad”

|

What makes Remedios the Beauty interesting from a naturist or nudist perspective is the fact that she sees nudity as merely practical. When she has to cover herself at all (living near Colombia’s Caribbean coast) she wears a loose shift that “resolved the problem of dress, without taking away the feeling of being naked, which according to her lights was the only decent way to be when at home” (248). She has no use for fashion or convention. She takes long baths and likes to feel the elements on her body. Most of her relatives view her as simple-minded, but this is contradicted by the opinion of her great uncle, Coronel Aureliano Buendía, who thinks she has an extraordinary lucidity that “permitted her to see the reality of things beyond any formalism” (214).

Take an old bedsheet and throw it over yourself – voila!, you are a ghost, easiest and maybe the oldest or most basic Halloween costume of all. Why do ghosts wear sheets, anyway? Maybe because the sheet is a shroud, the cloth that wraps a corpse. The cloth catches the spirit and animates its ethereal presence as it rises from the cadaver… It is a bolt of cloth that entombs us… metaphorically, it is the clothing that enshrouds us in life.

|

| Spencer Tunick, Mexico, 2012 |

Because we are not ghosts, we celebrate Halloween, and we remember our departed loved ones on El Día de los Muertos. We detect on the breeze–in the flickering candlelight, in the wafting aroma of chocolate or coffee or chrysanthemums–the spirit of someone who used to be alive, who used to be animate, animated (from the root for soul, anima). Because we are our bodies, because we are embodied and fleshed, we don over our flesh a costume–a ghost, a skeleton–to remind us that the end of all things is death. “The secret of life is that it stops,” said Kafka.

|

| Spencer Tunick, Mexico, 2012 |

Spencer Tunick’s 2012 photoshoot for el Día de los Muertos in Mexico features nude participants wearing translucent ghost shrouds, and it is a beautiful illustration of this idea: let us celebrate our living bodies while we can, while we are still alive – our living bodies that allow us to be animated, without shame, without fear. Underneath the sheets, and underneath the gravestone, we are all the same.

Exhausted, he knelt to the stage,

and felt his clothing like a cage.

He feebly made to rend his pants

and join the actors in their dance.

But short of breath, he could not grasp

a thing. “Please help,” he faintly gasped.

And quick the actors came to aid

the tailor to his tailor-made,

his birthday suit they helped expose.

At last he to his feet arose,

and spoke these words: “Dear playwright, friends:

Just like a needle, with thread, mends,

I lacked the sharp prick of your frank

display of chest and groin and flank

to understand my craft anew.

Your costumes I will make for you,

if you will stage your comedy

with clothes, but also nudity.”

It was agreed. And to the stage,

with all the tailor’s patronage,

attended crowds to see and learn

that to our bodies we should turn

not with disgust or shameful face

but awe and thanks and love and grace.

|

| Al natural, by Venezuelan playwright José Vicente Díaz Rojas |

Facebook has become Flankbook for naturists who brave its censorship vagaries. I haven’t even tried to accommodate the Nude Scribe site or its message to Facebook, but many intrepid naturists and naturist allies do attempt to yoke the massively popular site to their message of body acceptance and nude freedom. Some of them are actually quite successful, but also, almost all of them get censored by Facebook at one point or another, and punished with no images for a week, or even exile for a month. I do not support Facebook’s policy on images of nudity. Facebook censors already have been widely criticized for their Draconian reaction to photos of breastfeeding.

|

| Flankin’ on FB |

WHEREAS human beings are born naked into these bodies and thus begin, naked, the basic acts of life through the intake of breath and breast;

WHEREAS the freedom to move the physical volume of the body through the elements without encumbrance is a natural and healthful practice for body, mind, and spirit;

WHEREAS human beings have devised intricate processes for crafting and distributing cloth and clothing, for use in protecting or adorning the surface of the body’s physical volume;

WHEREAS human beings have also devised layers of social significance that accompany the range of bodily clothing displays, from nudity through the most elaborately crafted costumes;

WHEREAS these layers of social significance are constructed arbitrarily according to custom, context, and cultural expression; and enforced arbitrarily by political or ecclesiastical contrivance;

WHEREAS the recognition of the right to practice diverse cultural expressions, such as freedom of religion or political party and freedom to form a family, is inherent in the protection of human rights;

BE IT HEREBY DECLARED that FREEDOM OF DRESS, or the right to wear as much or as little clothing upon one’s body as one desires, including the right to manifest one’s body in its natural state, is a human right, to be fully protected by all governments for the betterment of humankind.

Today is a day to celebrate freedoms here in the United States, freedoms such as those depicted by the celebrated mid-20th-century American realist painter Norman Rockwell in his series called the Four Freedoms (clockwise from top left, below): Freedom of Speech, Freedom of Worship, Freedom from Want, and Freedom from Fear. These 1943 paintings, if not exclusively propaganda, were tied to government efforts to bolster faith in an American Way during World War II.

|

| Norman Rockwell, Four Freedoms, 1943 |

Notice that Freedom of Dress is not included here. I can imagine it to be parallel to the Freedom of Worship: just as we are free to follow any religion – or none at all, we should be free to follow any dress code – or none at all. Far from being unimportant or insignificant, Freedom of Dress undermines not just long-held taboos about the body, but also traditional ways of enforcing gender identity and social status through textiles. The idea would seem to have been too radical for 1943.

Seventy years later, its time is ripe. Beyond the very American traditions of naturist parks and free beaches that AANR and TNS have so admirably defended – venues for social nudism as a vital lifestype option in these United States – the more international character of the WNBR, WNGD, and nude street or campus protests shows a worldwide longing to split the seams of restrictive rules on clothing. It’s worth noting, too, that the mass nude shoots of American photographer Spencer Tunick have found wide acceptance overseas, often more so than in these United States.

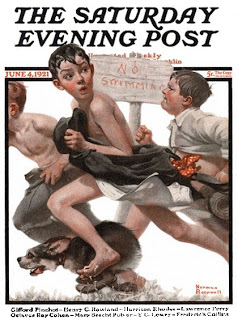

Can you imagine a Rockwell painting of a Tunick photograph? Perhaps that particular overlap between these two American artists is a stretch, but, returning to Rockwell, we can see that Freedom of Dress, in some ways, is not such a new idea. Another of his well-known paintings depicts some boys who have been skinny-dipping running away from the swimming hole, wet and struggling to dress: someone has discovered them. But the “No Swimming” sign, which is also the title of the 1921 painting, leads to the conclusion that the boys’ “crime” has been trespassing, not nudity. After all, in the early 20th century “swimming” was still largely synonymous with “bathing” in much of the country.

|

| Norman Rockwell, No Swimming, 1921 |

Is there also an element of shame to the boys’ partially dressed haste? We don’t know who has discovered them, so it’s anyone’s guess. But continued social movement toward Freedom of Dress is also, very powerfully, the movement toward Freedom from Shame.

Happy Independence Day!